Women in Gig Work, WageIndicator's fifth webinar on the plaform economy, started with Claire Hobden's speech on domestic workers' current conditions from a global perspective.

We followed up by introducing the best practices’ session.

As moderator and platform expert Martijn Arets underlined, sharing good examples can be an inspiring way to understand what has been done so far, and what can be improved. “When people see that something is possible, they don’t have the excuse to not do it anymore,” he rightly said.

Creating a new norm

Two outstanding speakers shared their experience on how they work on improving conditions for domestic workers.

Dawn Gearhart is the Director of Gig Economy Organizing at National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), an organization founded to advocate on behalf of domestic workers in the gig economy.

First, she described her previous experience with more than 3,000 app-based drivers. Then she got into the heart of the projects she is currently working on, regarding municipalities and platform companies in the United States to provide a voice for domestic workers.

- She mentioned Alia, the first portable benefits platform for domestic workers, that makes it easy for employers to contribute to the benefits for the house cleaner who works in their homes.

- In 2021, the National Domestic Workers Alliance also launched a first-of-its kind pilot program in cooperation with the online platform Handy. It succeeded in giving house cleaners in three states, Kentucky, Indiana and Florida, a minimum pay of $15 per hour, paid time off (paid for by Handy) and occupational accident insurance for workers on the job. It also created a formal process whereby house cleaners on Handy can discuss working condition concerns directly with Handy management.

- Another initiative worth mentioning is the Coronavirus Care Fund of 32 million dollars established by the NDWA, to provide emergency assistance for home care workers, nannies and house cleaners.

This case proves that there are multiple strategies to advocate for the position of the domestic worker. And that all these initiatives in the end strengthen each other. The strategy is to act (relatively) small and think big. This is because a victory on a small stage (like in one state) is the example for others. In this way, you create a new norm. And it shows that it takes a long breath and long-term commitment.

“We’ll keep pushing for federal legislation,” Gearhart concluded. “Limiting the commissions that platforms keep for themselves is another one of our goals. Different strategies need to be employed to create good and decent jobs”.

Hogaru: the platform that hires its cleaners

Next, we heard the inspiring testimony of Juan Sebastian Cadavid, CEO at Hogaru, an on-demand cleaning platform where cleaners are formally and legally employed by the company with all benefits.

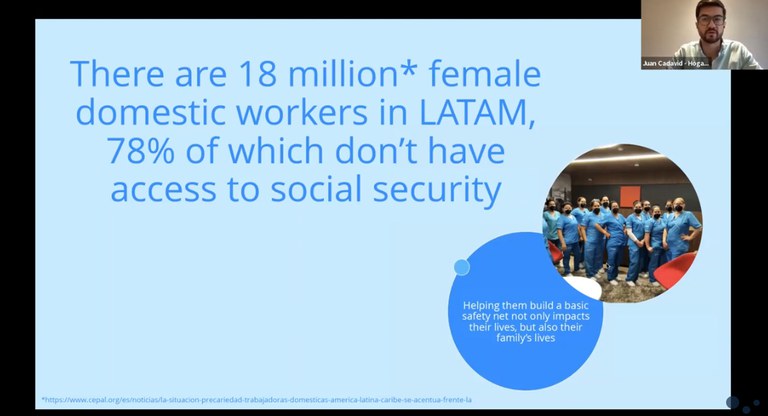

“Why does Hogaru exist? 18 million female domestic workers are estimated to live and work in Latin America. 78% of them do not have access to social security”.

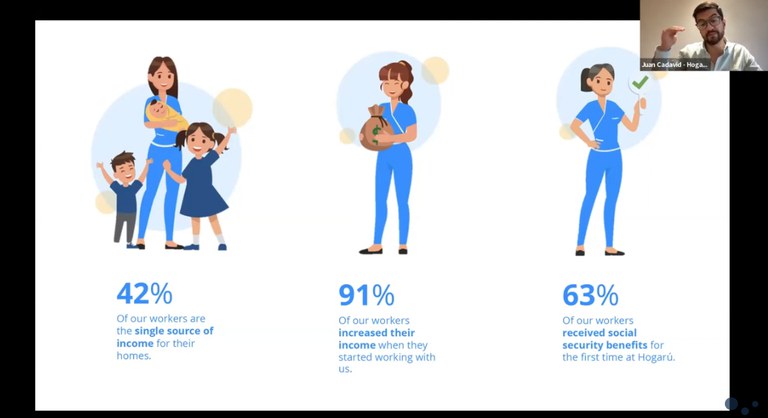

Hogaru started operations in 2015. 230,000 women had access to the Hogaru home care ecosystem during the past eight years, and 8,000 benefited directly from Hogaru.

Many platforms don’t invest in their workers, which leads to low commitment by workers and the platform having to spend money 'forcing' the worker to stay. What Hogaru shows is that it is possible to do good, and that it pays out when you invest in people. Platforms can indeed profit by creating commitment. As Cavadid said: “Spending on the well-being of workers should not be seen as a cost: it is an investment for future growth”.

However, platforms can have the best intentions, but good regulation and a government that takes responsibility is the key. Labor policies can further impact the local formalization rate. “Government policy can make or break a business, making social security mandatory without adding too much of a burden on the employee”, Cadavid added in his conclusions. “What we see is that our customers are willing to pay to help the formalization process”.

WOMEN IN GIG WORK: CONCLUSIONS

- Legal gaps, informality and low wages are common to both the traditional, offline domestic work and domestic work through digital platforms.

- A dichotomy standed out: domestic workers are more likely to work both very long or very short working hours with all possible downsides.

- Low pay is still an issue, as well as high commissions and costs of equipment, and lack of social protection which goes hand in hand with informality.

- There are still many narratives around the digitalization of the labor force and what platforms promise to workers. Yet, technology itself is not the solution to the inequalities and social problems we have in the traditional domestic sector.

- However, from the best practices we learned what is actually possible both from the private sector and workers’ organizations. Behind technology there are business decisions, values, and regulations. During this event, we saw the impact all these elements have on workers’ conditions and well being.

The second session of Women in Gig Work in March 2023 will focus on the gendered experiences of online web-based platform work, including on both freelance and microtask platforms. This will be the topic of the Women in Gig Part 2 webinar, scheduled for March 2023.