1. HOW TO ATTAIN THE LIVING WAGE IN MYANMAR

According to the expert for Myanmar we surveyed, Living Wages for an individual and for a household could be set around the lower bounds of the Living Wages calculated by the WageIndicator. Such a Living Wage could only be attained with the involvement of global actors or with coordinated actions of domestic manufacturers. The expert rather disagreed with the idea that the potential of the Myanmar government or individual domestic manufacturers would be able to achieve progress on reaching living wages without other support. He also doubted the usefulness of occasional end-consumer boycotts or sanctions embedded into international trade agreements to support the cause for living wages. Neither did the expert believe that further unionization could be instrumental in reaching living wages.

Under the open-door policy of the military regime, Myanmar’s garment exports grew steadily in the 1990s and the early 2000s. This growth lasted until 2003 when the US imposed sanctions against the regime and terminated all imports from 2004. The country’s garment exports to the US decreased to zero. At the same time exports to the European Union decreased. Japan and South Korea, who had not imposed sanctions on Myanmar during military rule, took over as the main export destinations. In the expectation of rapid democratization, the US lifted its import ban on Myanmar in November 2012, soon followed by the EU. In these conditions a general atmosphere of recovery developed and the prospects for the country’s garment sector actually seem rather rosy. Yet, consultants emphasize that production is hampered by poor infrastructure, like frequent power cuts, costly and unreliable logistics, and poor communication services. Also, labour shortages have come to the surface, and there is a lack of linkages: the country is yet not able to produce inputs for garment production according to the quality standards of international brands.

2. MINIMUM WAGES

A new law on minimum wages came into force in June 2013, and is a major social development in Myanmar. The law does not contain job-specific requirements or prescriptions for specific employee groups in the law. Garment employers wanted a lower minimum wage than applicable for other sectors, but the government did not take this into account and adopted a national minimum wage. An annual review process monitors the implementation of the law. The country has a minimum wage-setting tripartite committee; its decisions are not legally binding. The country expert contended that more academics and labour economists should be invited for consultations in the committee meetings.

3. COMPLIANCE

The Myanmar expert estimated between 31-40 per cent of garment industry workers to be members of trade unions. Unionization was seen as constrained by the opposition of employers and the global buyers as well as the lack of interest of workers to join. The expert noted that the concept of collective bargaining had just been introduced and was still new for Myanmar. There would plainly be a need for more advocacy and research on how collective bargaining might fit into the local context. While the expert did not consider labour legislation in Myanmar to be particularly permissive, its enforcement was regarded as weak. The Myanmar government has not yet paid much attention to positive industrial relations and the minimum wage law has been poorly implemented. Nevertheless, working relationships between the government and the trade unions were perceived as strong, as were those of trade unions and employer organizations. According to the expert, the government and the employer organizations have been the main influential actors in setting the minimum wage in Myanmar and in ensuring compliance with it and labour law generally. Trade unions were also important but had been less influential whilst the courts have played a relevant role in ensuring compliance.

4. WAGES IN CONTEXT IN MYANMAR

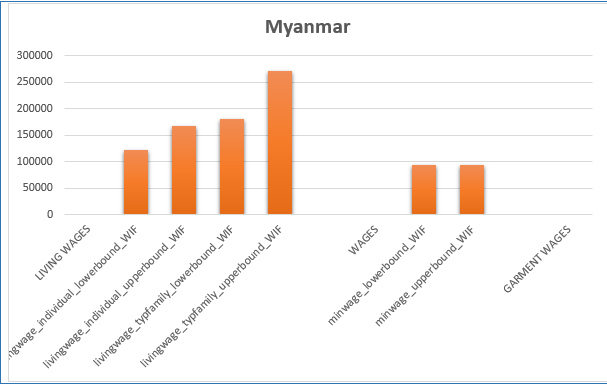

Figure 1 presents wage data for Myanmar: the monthly amounts of the living wages and the minimum wage (NMW). The LIVING WAGE section comprises the estimated living wages based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey for an individual and for a typical family, with lower and upper bounds. The WAGES section comprises the current NMW level. Unfortunately, for Myanmar no information on paid wages is currently available.

The figure and the underlying data show that the value of the 2015 NMW is just over 75 per cent of the lower bound living wage for an individual worker, and nearly 60 per cent of its upper bound equivalent.

Figure 1: Living wages and minimum wage in Myanmar, monthly amounts in Myanmar Kyat (MMK)

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

5. MYANMAR COMPARED

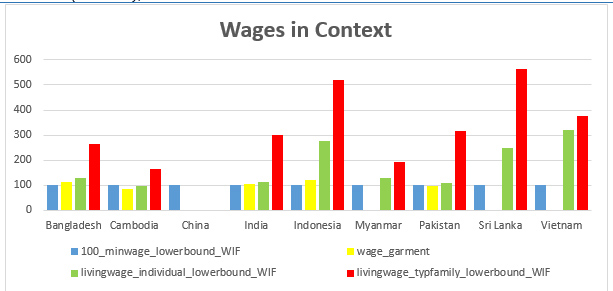

Figure 2 shows wages in context: the distances between the various wage levels calculated for the nine countries, setting the lower bound statutory minimum wage as 100 and relating this to the garment wages derived from official surveys as well as the estimated lower bound living wages for individuals and for typical families. In all five countries with official garment wages available, these wages are not far from the lower bound minimum wage; in two out of the five they even settle below that minimum wage, in Cambodia substantially and in Pakistan slightly.

In the eight countries (all except China) for which based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey living wages could be estimated, the relative levels of the lower bound living wage for individuals vary widely. Cambodia is the only country with this living wage settled below the lower bound minimum wage; for the other countries the individual living wage values range from 8 per cent (Pakistan) and 14 per cent (India) above the lower bound minimum wage up to 29 per cent (Bangladesh and Myanmar), 146 per cent (Sri Lanka), 174 per cent (Indonesia) and 219 per cent (Vietnam).

Figure 2: Wages in Context: Lower bound statutory minimum wage (=100, blue bars) related to the median garment wages (yellow bars), the lower bound living wage for individuals (green bars), and the lower bound living wage for typical families (red bars), nine countries

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia

This leaflet is based on a study undertaken for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Netherlands, on behalf of the Asian Living Wage Conference (ALWC) in Pakistan in 2016. The ALWC aims to engage Asian textile-producing countries in the initiatives of EU and US brands and multi-stakeholder initiatives to implement living wages. The Ministry has asked the WageIndicator Foundation to prepare input for the Conference by providing insight into the cost of living and related living wage levels in the garment industries in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

See Van Klaveren, M. (2016) Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April.

http://www.wageindicator.org/main/Wageindicatorfoundation/publications

WageIndicator Cost-of-Living and Living Wage levels calculations

WageIndicator maintains a Cost-of-Living survey with related Living Wage calculations, as well as a Work-and-Wages survey, a Minimum Wages Database, and a Labour Law Database for some 80 countries. For this report, WageIndicator intensified the Cost-of-Living data-collection in the nine countries, and interviewed experts from the nine countries regarding the hurdles to implement Living Wages.

Three features are critical in the WageIndicator Living Wage computations. First, they are based on the cost of living for a predefined food basket derived from the FAO database distinguishing 50 food groups with national food consumption patterns in per capita units (checked to ensure the percentage of calories from proteins is consistent with WHO balance diet), for housing and for transportation, with a margin for unexpected expenses. Second, data about prices of these items is collected through a survey. For this purpose, the Internet is used as it reaches out to large numbers of people. This WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey invites web visitors on all WageIndicator websites to complete the survey for a single item or for the list of items. The survey is a multi-country, multilingual, continuous web survey, with a printed version and an App for offline data-collection. Third, in determining a Living Wage, WageIndicator assumes the Living Wage for a typical family referring to the family composition most common in the country at stake, calculated on the respective fertility rates.

See for information: Guzi, M., and Kahanec, M. (2014) Wageindicator Living Wages, Methodological Note. Bratislava/Amsterdam: CELSI/Wage; Guzi, M., Kahanec, M., Kabina, T. (2016) Codebook of the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation

WageIndicator Foundation (www.wageindicator.org; office@wageindicator.org)

WageIndicator started in 2001 to contribute to a transparent labour market for workers and employers by publishing easily accessible information on a website. It collects, compares and shares labour market information through online and face-to-face surveys and desk research. It publishes the collected information on national websites, thereby serving as an online library for wage information, Labour Law, and career advice, both for workers/employees and employers. The websites attract a large audience, because they publish urgently needed but usually not easy accessible information, in 2015 resulting in more than 32 million visitors.