1. HOW TO ATTAIN THE LIVING WAGE IN SRI LANKA

The expert for Sri Lanka we surveyed set Living Wages for an individual and for a household slightly higher than the lower bounds of the Living Wages for an individual and a typical family calculated based on WageIndicator data. The expert noted that tripartite constituents were in the process of reviewing the Living Wage; the definition of the level of Living Wages was a combination of what the tripartite constituents were alluding to. The expert stated that the introduction of a Living Wage could strongly improve the situation of garment workers, although there was a possibility that this might lead to company closures due to relocation and to increasing unemployment. It could only be achieved with the involvement of global garment industry actors, including garment consumers. Occasional consumer boycotts supporting the local quest for living wages and buttressed by coordinated actions of domestic garment manufacturers would both be useful too. Similarly, coordinated regulatory actions of low-cost garment manufacturing countries could be instrumental. Individual actions of domestic garment manufacturers were assumed to be less effective, and so were sanctions embedded in international trade agreements, along with activities to encourage ethical consumption and further unionization.

In 1977 the Sri Lankan economy was liberalised and took the first steps towards export-oriented manufacturing. In the 2000s, the EU’s trade policies vis-a-vis Sri Lanka came into play. After the December 2004 tsunami, that killed 35,000 people in Sri Lanka, the EU decided to grant the country GSP Plus facilities with effect from July 2005. In these years, the country’s garment industry faced challenges such as the phasing out of the MFA in 2005 and later on the global financial crisis. In 2010 the EU decided to withdraw the GSP Plus facility from Sri Lanka on the basis of its alleged poor human rights record during the final stages of the war against the so-called Tamil Tigers, implying a serious setback for the industry. Garment employment a decrease, to an estimated 290,000 employed in 2015 of which over 250,000 women. Informed authors saw a number of hurdles to renewed growth of the Sri Lankan garment industry, like the existence of a small domestic textile industry and the poor state of the country’s infrastructure.

2. MINIMUM WAGES

The Wage Boards Ordinance regulates minimum wages in Sri Lanka. According to the ordinance, the Minister may establish a Wage Board for any trade, or any function or process in such trade. This gives autonomy to the government to increase the scope of the minimum wage. Currently 44 Wage Boards are in existence, with employers and workers represented in equal numbers. For the garment industry, in 2013-2015 separate minimum wage rates were in existence depending on skill grades. Yet, in March 2016 a bill was passed in parliament to have the minimum wage set at LKR 10,000 per month, plus some allowances, for all industries, including the garment manufacturing sector. According to the expert the influence of trade unions and the government on minimum wage-setting in Sri Lanka is considerable, whereas employer organizations have been seen to have medium influence.

3. COMPLIANCE

The expert surveyed noted that around 26 percent of the garment workers are currently covered by unions. According to the expert, union busting and the perception of trade unions as ‘troublemakers’ do not make them sufficiently attractive to garment workers, mostly women. Sri Lanka has collective agreements at national and/or regional level. Enterprise-level agreements are less widespread, and cover less than 10 per cent of the garment workers.

While the Ministry of Labour is moving towards an advanced labour inspection system, according to the expert quite some room remains for improving compliance. In particular, regulation and enforcement of labour law could be improved by more training of mediators, conciliators, and labour tribunal presidents, as well as by developing better social dialogue and negotiation skills amongst the social partners.

4. WAGES IN CONTEXT IN SRI LANKA

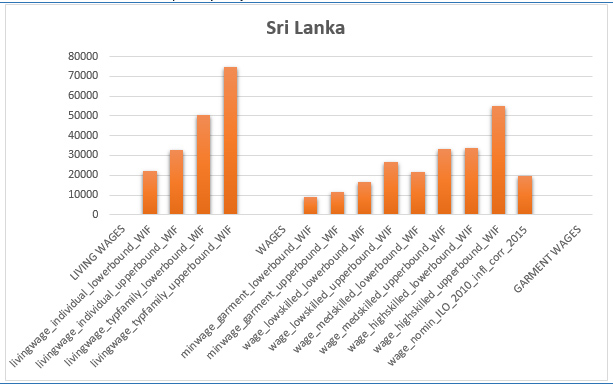

Figure 1 presents wage data for Sri Lanka: the monthly amounts of the living wages, the minimum wages and the total wages according to WageIndicator and ILO data. The LIVING WAGE section comprises the estimated living wages based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey for an individual and for a typical family, with lower and upper bounds. The WAGES section comprises two 2015 minimum wage levels, LKR 8,970 for the lower bound level (lowest grade/first year) and LKR 11,330 for the upper bound level (highest grade attainable in fifth year of employment). Based on WageIndicator 2015 data average wages are presented for low-, medium- and high-skilled workers, all with lower and upper bounds. The total nominal wage level based on the ILO Wage Database 2010 is included. For Sri Lanka no information on garment wages is available.

The figure and the underlying data show that the 2015 average wages for low-skilled are some 40 per cent higher than the upper bound minimum wage and nearly double the lower bound minimum wage. The distance between minimum wage levels and wages of medium- and high-skilled is even larger.. If corrected for inflation in 2010-2015, the overall wage level as captured by the ILO for 2010 would end up 20 per cent above the lower bound low-skilled wage for 2015. The estimated lower bound living wage for an individual is between the lower and upper bounds of the wages for low-skilled and about equal the lower bound wage level for medium-skilled; the upper bound would equal the upper bound medium-skilled wage or the lower bound high-skilled wage.

Figure 1: Living wages, minimum wages, and total wages in Sri Lanka, monthly amounts in Sri Lanka Rupees (LKR)

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

5. SRI LANKA COMPARED

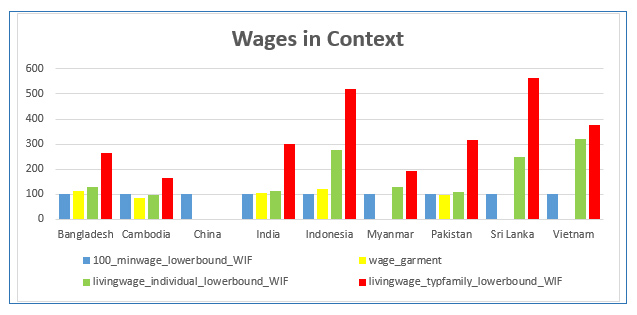

Figure 2 shows wages in context: the distances between the various wage levels calculated for the nine countries, setting the lower bound statutory minimum wage as 100 and relating this to the garment wages derived from official surveys as well as the estimated lower bound living wages for individuals and for typical families. In all five countries with official garment wages available, these wages are not far from the lower bound minimum wage; in two out of the five they even settle below that minimum wage, in Cambodia substantially and in Pakistan slightly.

In the eight countries (all except China) for which based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey living wages could be estimated, the relative levels of the lower bound living wage for individuals vary widely. Cambodia is the only country with this living wage settled (5%) below the lower bound minimum wage; for the other countries the individual living wage values range from 8 per cent (Pakistan) and 14 per cent (India) above the lower bound minimum wage up to 29 per cent (Bangladesh and Myanmar), 146 per cent (Sri Lanka), 174 per cent (Indonesia) and 219 per cent (Vietnam).

Figure 2: Wages in Context: Lower bound statutory minimum wage (=100, blue bars) related to the median garment wages (yellow bars), the lower bound living wage for individuals (green bars), and the lower bound living wage for typical families (red bars), nine countries

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia

This leaflet is based on a study undertaken for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Netherlands, on behalf of the Asian Living Wage Conference (ALWC) in Pakistan in 2016. The ALWC aims to engage Asian textile-producing countries in the initiatives of EU and US brands and multi-stakeholder initiatives to implement living wages. The Ministry has asked the WageIndicator Foundation to prepare input for the Conference by providing insight into the cost of living and related living wage levels in the garment industries in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

See Van Klaveren, M. (2016) Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April.

http://www.wageindicator.org/main/Wageindicatorfoundation/publications

WageIndicator Cost-of-Living and Living Wage levels calculations

WageIndicator maintains a Cost-of-Living survey with related Living Wage calculations, as well as a Work-and-Wages survey, a Minimum Wages Database, and a Labour Law Database for some 80 countries. For this report, WageIndicator intensified the Cost-of-Living data-collection in the nine countries, and interviewed experts from the nine countries regarding the hurdles to implement Living Wages.

Three features are critical in the WageIndicator Living Wage computations. First, they are based on the cost of living for a predefined food basket derived from the FAO database distinguishing 50 food groups with national food consumption patterns in per capita units (checked to ensure the percentage of calories from proteins is consistent with WHO balance diet), for housing and for transportation, with a margin for unexpected expenses. Second, data about prices of these items is collected through a survey. For this purpose, the Internet is used as it reaches out to large numbers of people. This WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey invites web visitors on all WageIndicator websites to complete the survey for a single item or for the list of items. The survey is a multi-country, multilingual, continuous web survey, with a printed version and an App for offline data-collection. Third, in determining a Living Wage, WageIndicator assumes the Living Wage for a typical family referring to the family composition most common in the country at stake, calculated on the respective fertility rates.

See for information: Guzi, M., and Kahanec, M. (2014) Wageindicator Living Wages, Methodological Note. Bratislava/Amsterdam: CELSI/Wage; Guzi, M., Kahanec, M., Kabina, T. (2016) Codebook of the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation

WageIndicator Foundation (www.wageindicator.org; office@wageindicator.org)

WageIndicator started in 2001 to contribute to a transparent labour market for workers and employers by publishing easily accessible information on a website. It collects, compares and shares labour market information through online and face-to-face surveys and desk research. It publishes the collected information on national websites, thereby serving as an online library for wage information, Labour Law, and career advice, both for workers/employees and employers. The websites attract a large audience, because they publish urgently needed but usually not easy accessible information, in 2015 resulting in more than 32 million visitors.