1. HOW TO ATTAIN THE LIVING WAGE IN VIETNAM

The expert for Vietnam we surveyed reckoned that the introduction of a Living Wage would basically improve the conditions of garment workers. It would not, he thought, lead to increasing unemployment or to lower exports from Vietnam and its impact would also be neutral regarding firm closures and garment production relocation. Yet, according to the expert, experience also demonstrated that if the transition towards a Living Wage was not accompanied by stricter law enforcement that could have adverse consequences for garment workers. The expert contended that adequate labour legislation and proper enforcement would greatly contribute to better wages and working conditions in the garment industry. At international level, occasional end-consumer boycotts, joint coordinated regulatory actions of garment-producing countries and sanctions embedded into international trade agreements linked to the attainment of Living Wages could all be supportive of the quest of garment workers in Vietnam.

In Vietnam, the ‘Doi Moi’ reforms of 1986 steered a path to a market-oriented economy. In the early 1990s, Vietnam’s export-oriented garment industry entered the US and European markets. In the 2000s and opposed notably to Myanmar, Vietnam enjoyed increasing access to international markets through its improved relations with the US. Around 2010, Vietnam started to make inroads into the quality-sensitive (and higher-value added) markets of Europe and Japan. The structure of the Vietnamese garment industry remains highly segmented. Until the early 2000s, large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominated. Though the SOEs have transformed to private or joint stock companies, small and medium-sized firms still go through hard times, remaining in dependent positions and mostly only carrying out outsourcing contracts. By international standards most of these firms are relatively small and under-financed, adding to the rather small basis of the Vietnamese garment export sector. For 2015 we estimated employment of the garment industry in Vietnam at 1.2 million, of which some 950,000 women employed.

2. MINIMUM WAGES

Vietnam has no separate minimum wage legislation; the general Labour Code 1994 regulates minimum wage fixing. The government determines a general minimum wage rate as well as rates for each region and, in principle, for each industry. It does so after consultation with the only legal trade union federation, VGCL (Vietnam General Confederation of Labour), and representatives of employers. Different minimum wages exist for different types of enterprises, i.e., domestic and foreign-owned (FIEs). Due to the lack of sectoral bargaining practice, currently only two sectoral sets of minimum wages are viable, including those for textile and garment firms insofar they are covered by the sectoral collective agreement. In 2010, this first sectoral agreement in the country came into being after careful preparation.

3. COMPLIANCE

In Vietnam, according to the expert 61 to 70 per cent of garment workers are union members. This seems quite high, though the situation is complicated due to the fact that besides the sectoral garment union, workplace unions in the industry also exist. If their members would be included, total union density in the garment industry may have ended up at at large 40 per cent. The expert regarded union influence on wages and working conditions as moderate. It has been recognized that the lack of a proper social dialogue has been one of the root causes of the considerable and increasing number of strikes taking place in Vietnam, with wage increases lagging behind cost of living increases as a second complex of causes.

The Better Work Vietnam program, starting in 2009 under guidance of the ILO, allows tracing compliance in the Vietnamese garment industry. In the 2014-15 sample the incidence of non-compliance concerning minimum wage payments was 38 per cent. A half-year earlier, half of the factories (51%) in the Better Work sample were found non-compliant on one or more regulations in the area of collective bargaining.

4. WAGES IN CONTEXT IN VIETNAM

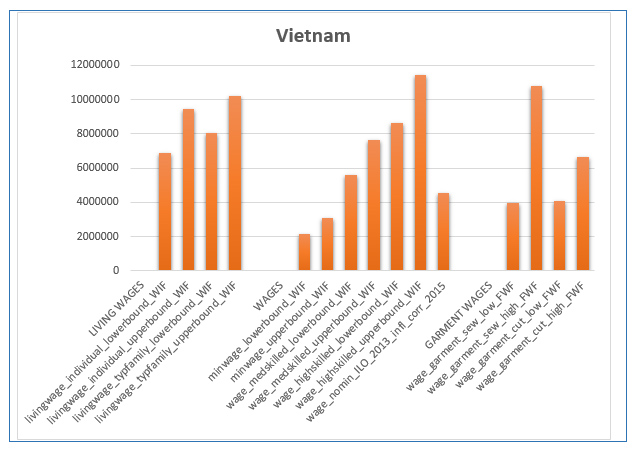

Figure 1 presents wage data for Vietnam. The LIVING WAGE section comprises the estimated living wages based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey for an individual and for a typical family, with lower and upper bounds. The WAGES section comprises two 2015 minimum wage levels: VND 2,150,000 for Region IV as the lower bound value and VND 3,100,000 for Region I (Hanoi) as upper bound. On the right-hand side, based on WageIndicator 2015 data average wages for two categories of workers are presented, that is, for medium- and high-skilled workers, both with lower and upper bounds. Next, the total average wage level based on the ILO Wage Database 2013 is included, corrected for inflation in 2013-2015. The GARMENT WAGES section comprises the wages paid in 2015 in the garment industry, for four categories of workers based on Fair Wear Foundation (FWF) information. These wages are presented for region I.

The figure and the underlying data show that the lower bound garment wages are nearly double the lower bound MW and also 40-50 per cent above the upper bound MW. The lower bounds of the garment wages are some 30 per cent below the lower bound medium-skilled wage level. For 2015 the inflation-corrected average wage would be some 10 per cent higher than the lower bound garment wages. The estimated lower bound living wage for an individual is some 40 per cent higher than the lower bound garment wages and matches the higher bound garment wage for cutting jobs. The upper bound living wage for an individual is 2.3 times the lower bound garment wages and over 3 times the upper bound minimum wage.

Figure 1: Living wages, minimum wages, total wages and garment wages in Vietnam, monthly amounts in Vietnam Dong (VND))

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

5. VIETNAM COMPARED

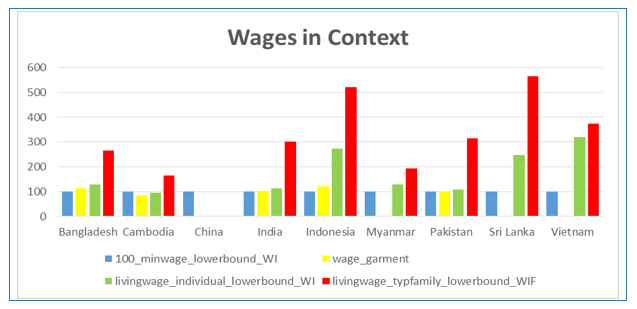

Figure 2 shows wages in context: the distances between the various wage levels calculated for the nine countries, setting the lower bound statutory minimum wage as 100 and relating this to the garment wages derived from official surveys as well as the estimated lower bound living wages for individuals and for typical families. In all five countries with official garment wages available, these wages are not far from the lower bound minimum wage; in two out of the five they even settle below that minimum wage, in Cambodia substantially and in Pakistan slightly.

In the eight countries (all except China) for which based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey living wages could be estimated, the relative levels of the lower bound living wage for individuals vary widely. Cambodia is the only country where this living wage settles slightly below the lower bound minimum wage; for the other countries the individual living wage values range from 8 per cent (Pakistan) and 14 per cent (India) above the lower bound minimum wage up to 29 per cent (Bangladesh and Myanmar), 146 per cent (Sri Lanka), 174 per cent (Indonesia) and 219 per cent (Vietnam).

Figure 2: Wages in Context: Lower bound statutory minimum wage (=100, blue bars) related to the median garment wages (yellow bars), the lower bound living wage for individuals (green bars), and the lower bound living wage for typical families (red bars), nine countries

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia

This leaflet is based on a study undertaken for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Netherlands, on behalf of the Asian Living Wage Conference (ALWC) in Pakistan in 2016. The ALWC aims to engage Asian textile-producing countries in the initiatives of EU and US brands and multi-stakeholder initiatives to implement living wages. The Ministry has asked the WageIndicator Foundation to prepare input for the Conference by providing insight into the cost of living and related living wage levels in the garment industries in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

See Van Klaveren, M. (2016) Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April.

http://www.wageindicator.org/main/Wageindicatorfoundation/publications

WageIndicator Cost-of-Living and Living Wage levels calculations

WageIndicator maintains a Cost-of-Living survey with related Living Wage calculations, as well as a Work-and-Wages survey, a Minimum Wages Database, and a Labour Law Database for some 80 countries. For this report, WageIndicator intensified the Cost-of-Living data-collection in the nine countries, and interviewed experts from the nine countries regarding the hurdles to implement Living Wages.

Three features are critical in the WageIndicator Living Wage computations. First, they are based on the cost of living for a predefined food basket derived from the FAO database distinguishing 50 food groups with national food consumption patterns in per capita units (checked to ensure the percentage of calories from proteins is consistent with WHO balance diet), for housing and for transportation, with a margin for unexpected expenses. Second, data about prices of these items is collected through a survey. For this purpose, the Internet is used as it reaches out to large numbers of people. This WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey invites web visitors on all WageIndicator websites to complete the survey for a single item or for the list of items. The survey is a multi-country, multilingual, continuous web survey, with a printed version and an App for offline data-collection. Third, in determining a Living Wage, WageIndicator assumes the Living Wage for a typical family referring to the family composition most common in the country at stake, calculated on the respective fertility rates.

See for information: Guzi, M., and Kahanec, M. (2014) Wageindicator Living Wages, Methodological Note. Bratislava/Amsterdam: CELSI/Wage; Guzi, M., Kahanec, M., Kabina, T. (2016) Codebook of the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation

WageIndicator Foundation (www.wageindicator.org; office@wageindicator.org)

WageIndicator started in 2001 to contribute to a transparent labour market for workers and employers by publishing easily accessible information on a website. It collects, compares and shares labour market information through online and face-to-face surveys and desk research. It publishes the collected information on national websites, thereby serving as an online library for wage information, Labour Law, and career advice, both for workers/employees and employers. The websites attract a large audience, because they publish urgently needed but usually not easy accessible information, in 2015 resulting in more than 32 million visitors.