1. HOW TO ATTAIN THE LIVING WAGE IN INDONESIA

The experts for Indonesia we surveyed estimated Living Wages for individuals slightly respectively considerably lower than the lower bound Living Wages calculated by the WageIndicator, and family-based Living Wages slightly above the lower bound WageIndicator-based living wage for a typical family. The experts strongly agreed that occasional end-consumer boycotts and further unionization would both be instrumental to support wage increases towards the level of the Living Wage. They also agreed that coordinated regulatory actions of low-cost garment manufacturing countries would offer strong support to the quest for living wages. This fitted with their acknowledgement that the living wage could only be attained with the involvement of global actors. In addition, some coordinated action from domestic garment manufacturers coupled with activities to encourage ethical consumption among end-consumers, was also seen as supportive. Experts saw less potential influence stemming from sanctions embedded in international trade agreements.

In the 1980s, Indonesia’s government attracted considerable amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) into low-wage, labour-intensive manufacturing industries. Thousands of mainly young female workers entered the workforce in the textile, garment, and footwear industries producing largely for export. In the early 1990s, the government declared garment manufacturing to be a ‘strategic industrial sub-sector.’ After 2000 Indonesia’s garment industry continued to expand but the phasing out of the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) in 2005 meant a major setback. International buyers concentrated on larger, more efficient suppliers and shifted production to China and Vietnam. From 2007 onwards, Indonesia’s share in world garment exports decreased while garment employment fell before stabilizing at an estimated 1.4 million employed of which over 900,000 women. In the 2010s, in response to relatively strong wage increases in the greater Jakarta area, investors shifted garment production within Indonesia to Central Java.

2. MINIMUM WAGES

Indonesia has separate legislation for minimum wage fixing. Until quite recently, minimum wages were set at provincial level and, in accordance with the National Government’s Wage Policy, further set at sectoral levels or by provincial governors following recommendations of Provincial Wage Councils and District Wage Councils. By a New Regulation as of October 2015 the Indonesian government has enacted a new mechanism to determine minimum wages. The trade unions fiercely protested against this regulation, arguing they have been excluded from the annual wage negotiation process. According to the experts surveyed, the government was already most influential in minimum wage setting in the Wage Councils, and by now that position seems to have been strengthened.

3. COMPLIANCE

Union density is at a rather low level in Indonesia, though according to the surveyed experts in the garment industry between 40 and 50 per cent. This may have to do with the counting of only permanent workers. Experts’ opinions diverged when assessing the influence of trade unions on wages and working conditions but they were unified in the perception that trade unions had moderately weak relationships with the government, with employer organizations and with global buyers. Only factory-level collective agreements are in place in Indonesia, and according to the experts, 11-20 per cent of garment workers may be covered by such agreements.

The experts highlighted that a considerable part of Indonesian garment factories did not comply with labour law, in particular with wage and related regulations. This is by and large supported by the outcomes of the Better Work Indonesia (BWI) program. For 2013-14, a BWI evaluation found non-compliance rates to be 37 per cent for not paying the minimum wage and as high as 75 per cent for not (adequately) paying overtime. Though legally employers are prohibited from paying wages lower than the minimum wage, and sanctions are severe, violations have hardly ever been brought to court.

4. WAGES IN CONTEXT IN INDONESIA

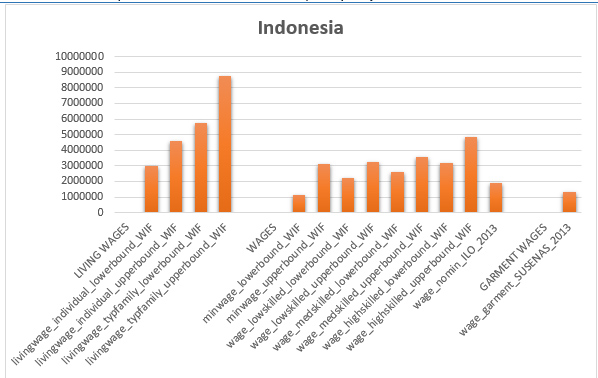

Figure 1 presents wage data for Indonesia: the monthly amounts of the living wages, the minimum wages, the total wages in Indonesia according to WageIndicator and ILO data, and the wages of garment workers. The LIVING WAGE section comprises the estimated living wages based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey for an individual and for a typical family, with lower and upper bounds. The WAGES section comprises two 2015 minimum wage levels, those of Central Java (lower bound) and West Java (upper bound). Based on WageIndicator 2015 data average wages for three categories of workers are presented: for low-, medium- and high-skilled workers, all with lower and upper bounds. The total average wage level based on the ILO Wage Database 2013 is also included. The GARMENT WAGES section includes Indonesia’s garment wages based on the 2013 National Socioeconomic Survey (SUSENAS).

The figure and the underlying data show that the average garment wage is 20 per cent above the lower bound minimum wage but over 40 per cent below the upper bound MW level. It is also much lower than the overall wages for all categories based on the WageIndicator and 30 per cent below the ILO-based average wage level. With the higher bound high-skilled wage 2.1 times the lower bound low-skilled level, wage dispersion is limited. The paid wages are clearly low. The lower bound living wage for an individual is double the inflation-corrected 2015 garment wage. The wages of all worker groups, regardless their skill levels, do not meet the lower bound level of the living wage for a typical family, let alone its upper bound level.

Figure 1. Living wages, minimum wages, total wages and garment wages in Indonesia, monthly amounts in Indonesian Rupiah (IDR)

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

5. INDONESIA COMPARED

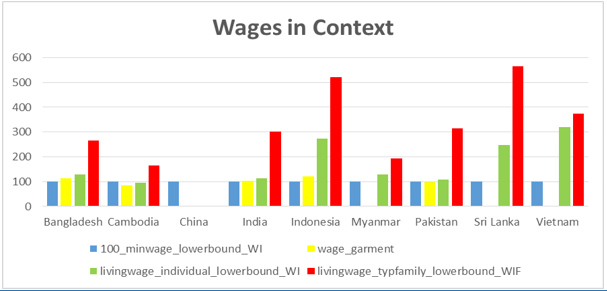

Figure 2 shows wages in context: the distances between the various wage levels calculated for the nine countries, setting the lower bound statutory minimum wage as 100 and relating this to the garment wages derived from official surveys as well as the estimated lower bound living wages for individuals and for typical families. In all five countries with official garment wages available, these wages are not far from the lower bound minimum wage; in two out of the five they even settle below that minimum wage, in Cambodia substantially and in Pakistan slightly.

In the eight countries (all except China) for which based on the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey living wages could be estimated, the relative levels of the lower bound living wage for individuals vary widely. Cambodia is the only country where this living wage settles slightly below the lower bound minimum wage; for the other countries the individual living wage values range from 8 per cent (Pakistan) and 14 per cent (India) above the lower bound minimum wage up to 29 per cent (Bangladesh and Myanmar), 146 per cent (Sri Lanka), 174 per cent (Indonesia) and 219 per cent (Vietnam).

Figure 2: Wages in Context: Lower bound statutory minimum wage (=100, blue bars) related to the median garment wages (yellow bars), the lower bound living wage for individuals (green bars), and the lower bound living wage for typical families (red bars), nine countries

Source: Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April 2016.

Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia

This leaflet is based on a study undertaken for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Netherlands, on behalf of the Asian Living Wage Conference (ALWC) in Pakistan in 2016. The ALWC aims to engage Asian textile-producing countries in the initiatives of EU and US brands and multi-stakeholder initiatives to implement living wages. The Ministry has asked the WageIndicator Foundation to prepare input for the Conference by providing insight into the cost of living and related living wage levels in the garment industries in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

See Van Klaveren, M. (2016) Wages in Context in the Garment Industry in Asia. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation, April.

http://www.wageindicator.org/main/Wageindicatorfoundation/publications

WageIndicator Cost-of-Living and Living Wage levels calculations

WageIndicator maintains a Cost-of-Living survey with related Living Wage calculations, as well as a Work-and-Wages survey, a Minimum Wages Database, and a Labour Law Database for some 80 countries. For this report, WageIndicator intensified the Cost-of-Living data-collection in the nine countries, and interviewed experts from the nine countries regarding the hurdles to implement Living Wages.

Three features are critical in the WageIndicator Living Wage computations. First, they are based on the cost of living for a predefined food basket derived from the FAO database distinguishing 50 food groups with national food consumption patterns in per capita units (checked to ensure the percentage of calories from proteins is consistent with WHO balance diet), for housing and for transportation, with a margin for unexpected expenses. Second, data about prices of these items is collected through a survey. For this purpose, the Internet is used as it reaches out to large numbers of people. This WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey invites web visitors on all WageIndicator websites to complete the survey for a single item or for the list of items. The survey is a multi-country, multilingual, continuous web survey, with a printed version and an App for offline data-collection. Third, in determining a Living Wage, WageIndicator assumes the Living Wage for a typical family referring to the family composition most common in the country at stake, calculated on the respective fertility rates.

See for information: Guzi, M., and Kahanec, M. (2014) Wageindicator Living Wages, Methodological Note. Bratislava/Amsterdam: CELSI/Wage; Guzi, M., Kahanec, M., Kabina, T. (2016) Codebook of the WageIndicator Cost-of-Living Survey. Amsterdam: WageIndicator Foundation

WageIndicator Foundation (www.wageindicator.org; office@wageindicator.org)

WageIndicator started in 2001 to contribute to a transparent labour market for workers and employers by publishing easily accessible information on a website. It collects, compares and shares labour market information through online and face-to-face surveys and desk research. It publishes the collected information on national websites, thereby serving as an online library for wage information, Labour Law, and career advice, both for workers/employees and employers. The websites attract a large audience, because they publish urgently needed but usually not easy accessible information, in 2015 resulting in more than 32 million visitors.